“Building our Multistakeholder Digital Future” was the theme of the 19th edition of the UN-based Internet Governance Forum (IGF). It attracted more than 11.000 participants (Offline and Online) from all over the world in Riyadh/Saudi Arabia, December 15-19, 2024. In the 307 plenaries, workshops, open fora, lightening talks and other conversations in the meeting rooms and the lobby halls of the King Abdulaziz International Conference Center (KAICC), nearly everything that is related to the evaluation and the use of today’s and tomorrow’s Internet, was discussed: Affordable access to the Internet, digital divide, Internet fragmentation, digital economy, cybersecurity, cybercrime, human rights, data protection, freedom of expression, artificial intelligence, but also WSIS+20, the Sao Paulo Multistakeholder Guidelines and the Global Digital Compact. The IGF proved what the mothers and fathers of the IGF anticipated in 2005: The world needs such a global marketplace for the exchange of ideas and information where everybody is welcome and can participate in open and free debates on equal footing. In 2005, the Internet had less than 500 million users; in 2025, we have more than 5 billion people online. But two billion are still offline.

IGF as the primary Multistakeholder Platform

In his video speech, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres remembered that the recently adopted Global Digital Compact (GDC) recognized the Internet Governance Forum as “the primary multistakeholder platform for discussing Internet governance issues.” Guterres called the GDC “the blueprint for humanity’s digital future. It’s the first comprehensive framework of its kind, based on a simple but important principle: Digital technology must serve humanity—not the other way around” And he closed with a call for action: “Together, let’s keep building an open, free and safe Internet for all people.”

The opening speech was given by the minister of communications and information technology from Saudi Arabia, Abdullah Alswaha. Previous IGFs were opened by presidents or prime ministers of the host country, such as Emmanuel Macron in Paris (2018), Angela Merkel in Berlin (2019), Andrzej Duda in Katowice (2021), Abiy Ahmed in Addis Ababa (2022) and Fumio Kishida in Kyodo (2023). However, Mohamed bin Salmans’ picture appeared on the screen after the minister had finished his remarkable speech, in which he called for closing the “Digital North-South Gap.” He said: “We are talking about a gap in computing capacity of about 63GW, where only a handful of nations can deliver that. We are talking about a 10 million shortage between data scientists, cybersecurity professionals and AI professionals to close down. We need to tackle the algorithmic divide, the data and the compute divide. We need an algorithm to make sure that we are helpful, honest, and harmless, to make sure that there is no bias that leaves anyone behind, or an AI or a data scientist inserting and hard-coding a guardrail to exclude any of us.”

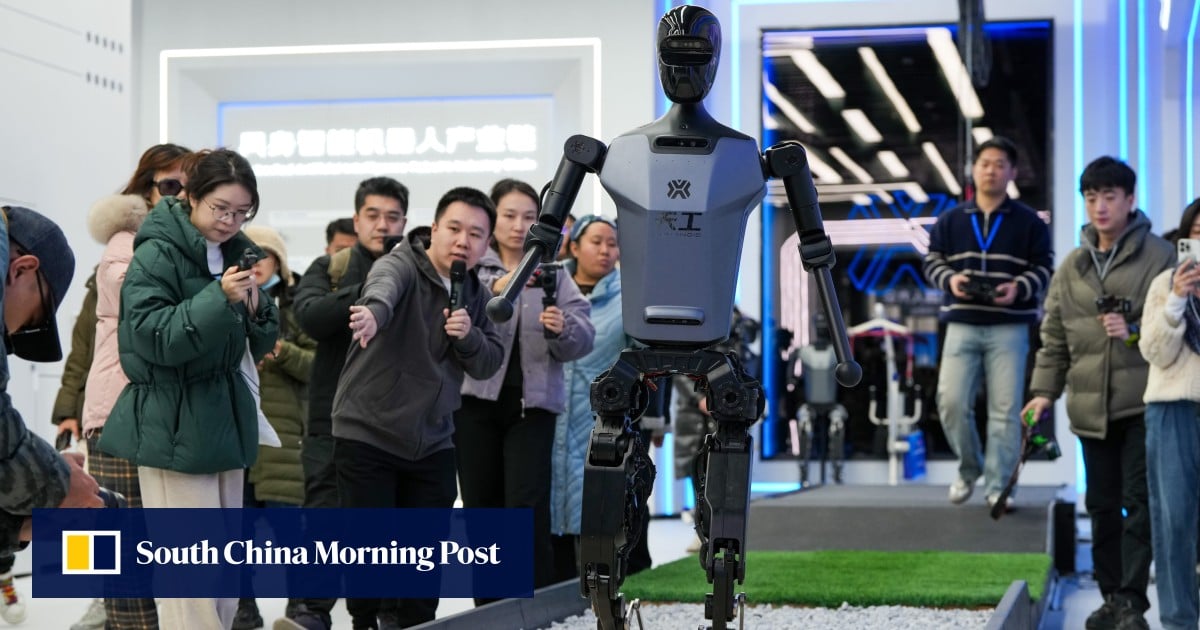

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence was naturally a main theme of IGF 2024. In more than 30 sessions, nearly all aspects of AI were discussed: AI Ethics, AI Regulation, AI Governance, AI and Blockchain, AI and Biometrics, AI and business models, AI in health and transportation services, AI weapons, AI as a subject of diplomatic negotiations.

More than a dozen out of the 57 “Riyadh IGF Message” are dealing with AI. One of the messages says: “Governance of AI is not a ‘nice to have’. Minimizing the risk of AI is crucial, but it is equally important to focus on tools that balance AI innovation and regulation. Overregulation can hinder AI’s potential to benefit humanity and the environment, yet, we should not compromise on ethical standards, tackling biases or ensuring privacy.” There was a call for accountability, transparency and explainability and a warning to avoid “regulatory fragmentation” across the “AI supply chain”.

The UN presented its plans for the new AI Panel and the AI Dialogue; the OECD offered insights into its AI Observatory and the work of the Global Alliance on AI; the EU explained its AI Act, the Council of Europe its AI Convention, the ITU its AI for Good Summit, the G7 the AI Hiroshima Process and UNESCO its Recommendation on AI Ethics. All these presentations were remarkable. However, the growing number of venues for AI Governance discussions risk leading to fragmentation, duplication and a waste of resources. It can also lead to a deepening of the North-South AI Gap because many developing countries do not have the capacity to follow all those AI discussion processes. They risk being sidelined.

For the first time, the IGF discussed also the military aspects of AI. The Austrian government, which is the sponsor of a related resolution in the UN General Assembly, organized an Open Forum on “Autonomous Weapon Systems” (AWS) under the title “The Oppenheimer Moment”. Diplomats from Austria, the Netherlands and the US, who negotiate the issue in the UN and the GGE LAWS, discussed with technical experts and civil society organizations such as the Global Commission on Responsible Artificial Intelligence in the Military Domain (GC REAIM), Amnesty International or Stop Killer Robots, whether one can compare the nuclear arms race after the dropping of the Hiroshima bomb in 1945 with today’s AWS arms race. And they discussed the pros and cons of an international AWS Treaty, as proposed by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres for 2026.

In another workshop, the dean of Argentina’s University of Defence chaired a discussion where the question was debated: how does AI change the nature of war, and what does it mean for the training of military personnel? And a Russian expert showed during a Lightening Talk video how drones are operating on the battlefield in the Ukrainian war.

One controversial issue was the definition of AI Governance. What are the differences between Internet Governance, Data Governance, Digital Governance, Cyber Governance, ICT Governance and now AI Governance? One proposal was to speak generally about “governance in the digital age” and to identify the specifics in different areas such as data, cyber or AI. There is no need to reinvent the wheel and introduce a new language. One could use the broad definition of “Internet Governance” from the Tunis Agenda as a basis. The main elements of the Tunis definition—a. a multistakeholder approach by including governments, business, civil society and the technical community, b. a cooperative approach with regard to policy development and decision making and c. a comprehensive approach by including both technical and policy aspects—are not only relevant for Internet Governance in the narrow sense, but for all forms of “governance in the digital age”. With other words, it makes a lot of sense to use the Tunis definition as a starting point for a specific definition of AI Governance.

WSIS+20

It was obvious that the forthcoming review of the UN World Summit of the Information Society (WSIS+20) played a central role. The mandate of the IGF is limited until 2025, and the WSIS+20 has to decide on the future of the IGF. But WSIS+20 is much more than the renewal of the IGF mandate. Many voices argued in Riyadh that the renewal of the IGF mandate should be seen as a more technical task after the GDC has recognized it as “the primary multistakeholder platform for discussing internet governance issues”. The GDC was adopted by the heads of states of 193 UN members. There is no need to reopen the issue. The IGF renewal should not be politisized or misused as a “bargaining chip” in geo-political arm twisting.

The IGF is a worldwide recognized success story. It has its weaknesses, which are to a high degree rooted in its poor budget. There is no need to open a discussion about the details of the mandate. Article 72 of the Tunis Agenda is comprehensive and flexible enough to deal also with new emerging digital problems of the next decade.

What is needed is a stable and secure financing mechanism. Such a mechanism has to remain diversified to avoid that someone (governments or business) can “buy” the IGF. All stakeholders are invited and should contribute, according to their possibilities. But it is a shame, that the big Internet corporations, which are now defined in the EU context as “Very Large Online Platforms” (VLOPS) contribute only with minimal checks to the IGF budget. VLOPS are big beneficiaries of a safe and stable technical and political Internet environment. It should be part of their “Corporate Social Responsibility” (CSR) to support the IGF. Investopedia defines CSR as “a business model that helps a company be socially accountable to itself, its stakeholders, and the public”. TikTok, Meta, Google, Apple, Alibaba, Microsoft etc. do you hear this? You are welcome to join the IGF community with your money.

But the bigger challenge for WSIS+20 will be the review of the 16 WSIS Action Lines and how these WSIS Action Lines can be better linked to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Also, this was discussed in Riyadh. One problem is, that the WSIS Action Lines and the SDGs are organized in two different processes by different people in New York and Geneva, with only a low level of interaction.

In 2015, when the “Milenium Development Goals” (MDGs) were reviewed and substituted by the SDGs, the negotiators in New York were rather ignorant with regard to the WSIS Action Lines and did not realize, that the world until 2030 will be a digital world. Some of the SDGs from 2015 have a “digital dimension”, but the SDGs as a whole do not have a strong digital chapter. This has to be changed until 2030, when the SDGs has to be reviewed. WSIS+20 is now an opportunity to build stronger bridges and to enhance to SDGs beyond 2030 into something like “Digital Development Goals” (DDGs).

As said above, the WSIS process is based in Geneva, the SDG process in New York. And as one could have seen recently during the negotiations around the Global Digital Compact, diplomats in Geneva and New York are ticking differently, if it comes to issues related to the evolution and the use of the Internet and the differences between multilateral and multistakeholder cooperation. However, solving global problems in the age of cyber interdependence requires a comprehensive approach. In other words, WSIS+20 is also a chance to bring different cultures and stakeholders in a new way together and to promote a better understanding between “New York” and “Geneva”

Global South

The call of Saudi’s minister Abdullah Alswaha, to close the gap between the Global South and the Global North was another main theme. This IGF did see a substantial decrease in participants from the “Global South”. They were in a majority. Less than 20 percent of the 11.000 registered participants came from the “Global North.” The 56 IGF Riyadh Messages include recommendations like “how to improve affordable access to services and devices, obtainable digital literacy and skills, and equal occupancy of the online space by both man and women, boys and girls, young and old, urban and rural, local and global communities”. The IGF messages recognized also that “cost of Internet access remains one of the main barriers to inclusion of the unconnected.”

With other words, also here money is a problem and a key factor. And also here, there is a need to find creative and innovative solutions. Certainly, the “Global North” has a special responsibility and should do more. And it is also better to invest money into future-oriented digital projects in the South than to waste it in wars in the North. But among the countries, belonging to the “Global South”, there are meanwhile next to the traditional poor countries also rich one’s. The Gulf countries as Quatar, UAE or Saudi Arabia invest a lot into modernizing their societies, including into big and costly sports events to improve their images. Substantial contributions to the “Universal Service Funds (USF) to promote digital education, the development of digital public infrastructure and the stimulation of AI start-ups in the Global South would also contribute to a better image. As one of the IGF messages says: “Significant investments, particularly through the Universal Service Funds (USF), drive digital inclusion”.

Looking Forward

The IGF in Riyadh was a good one. When the UN decided to give the 2024 IGF to Saudi Arabia, not everybody was excited. Some civil society groups, such as “Access Now”, and in particular women’s organisations and the LGBTQ+ community, referred to the violation of human rights and called for a boycott. And indeed, the participation of civil society organisations decreased by 13 percent compared wih the IGF 2023 and reached a low level of 11 percent of the total of all participants.

The host country was obviously aware and wanted to avoid “bad news”. It tried to present Saudi Arabia as future-orientied and as an open country, where women play a central role, especially in IT and AI. One-third of the participants of the IGF 2024 were female. The Secretary General of the “Digital Cooperation Organisation” (DCO), Deemah Al Yahya from Saudi Arabia, is an energetic woman who encourages girls in the gulf region to leapfrog into the AI age. Inside the convention center, one could see everything, from the Niqab and Abaya to Jeans and Hotpants. Everybody could ask every question. It was not a “censored IGF”, as it was feared by some groups. But everything was under control. Some observers did label it as a “curated IGF”. And unusual for the IGF, where “participation on equal footing” is a key cultural tradition, the Riaydh IGF had a “hierarchy” with a first class (VIP), a business class (L-Badges) and an Economy Class (P-badges).

After Riyadh, the IGF can certainly celebrate another success. But there is no question that it needs further improvement. In 2019, the UN High Level Panel on Digital Cooperation recommended an IGF+. How much of the “Plus” has been achieved so far?

Looking back, some substantial steps have been taken in the last five years. The IGF now has, on a regular basis, a governmental and parliamentarian track. Another track for judges, a “dedicated IGF judiciary track” was proposed. The IGF has broadened its institutional basis by the IGF Leadership Panel (LP). The “Output” with the IGF Messages, the IGF Chairs Report and the numerous transcripts and summaries from the hundreds of sessions is substantial and plays a growing role as a source of inspiration both for diplomatic negotiations, business plans and actions of civil society organisations. The establishment of the Office of the Secretary General’s Envoy on Technology (OSET) has created new opportunities to strengthen the IGF. All this is good.

But looking forward, there is still a lot to do to enhance relevance and efficiency. The hundred pages of “Outcome” are confusing. Shorter “Executive Summaries” could help to bring clear messages directly to the right venue, such as diplomatic negotiation rooms or CEO’s offices. The Leadership Panel could play a more active role in linking the digital discussion spaces to the digital decision-making places. In the IGF communication strategy there is room for improvement. The IGF takes place rather outside of the world news. This is bad.

The next IGF is scheduled for Oslo in Norway, June 23-27, 2025. This will be a crucial moment. In September 2025, the WSIS+20 final negotiations start in New York.