At her husband’s funeral in 1963, Myrlie Evers heard NAACP executive director Roy Wilkins say, “Medgar Evers believed in his country. It remains to be seen whether his country believes in him.”

Later today, his country will declare its confidence in him when the family of Mississippi’s slain NAACP leader receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor.

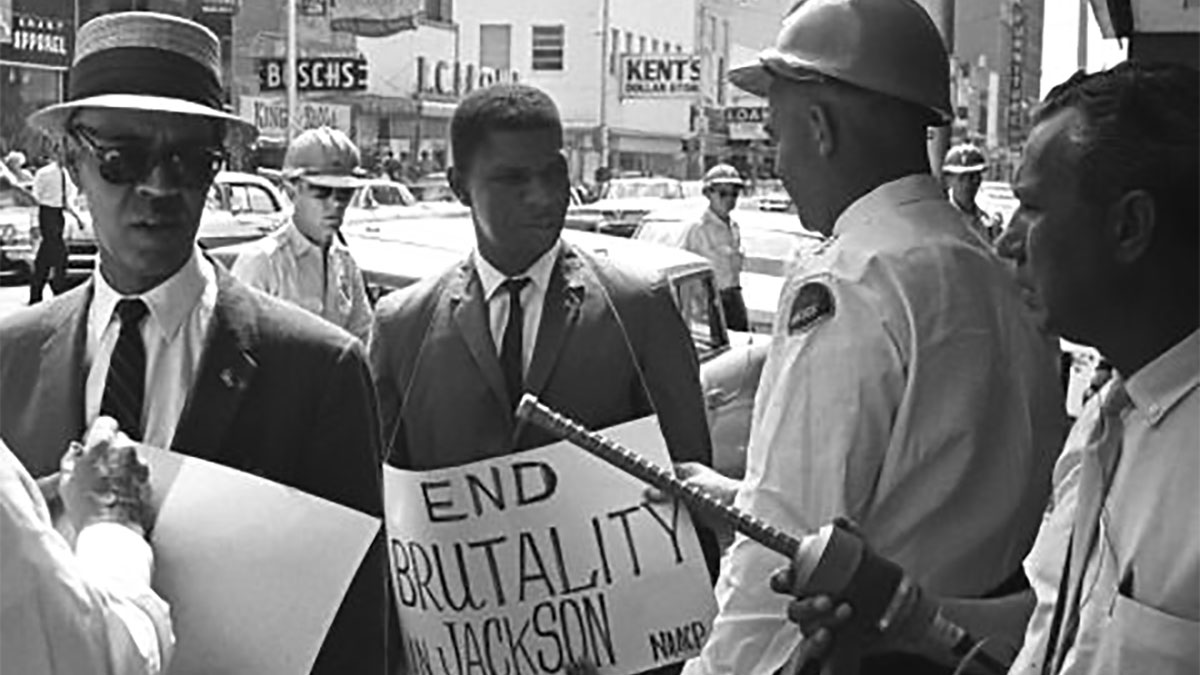

But Medgar Evers was more than a civilian. He fought the Nazis in World War II, only to return home and fight racism, this time in the form of Jim Crow, which barred black Mississippians from the polls.

On his 21st birthday, he and other black war veterans went to vote at the Decatur courthouse, where they were greeted by armed white men.

Afterward, he vowed that he would never be defeated again and would continue to fight by joining others dedicated to the cause of the civil rights movement.

“The movement for equality was always on his mind, and the denial of his right to vote by whites in his hometown was just one cog in the wheel of injustice, a wheel which he was determined and determined to break,” said Michael Vinson Williams, author of “Medgar Evers: Mississippi Martyr.”

Myrlie Beasley met Medgar Evers on the first day of her freshman year at Alcorn A&M College in the fall of 1950. As she leaned against a lamp post, she said he told her to be careful, ” You might be shocked.”

And she was shocked when she fell in love and married him a year later. He was one of those veterans her family had warned her about. And he was involved in the movement his family had avoided.

She joined him in the fight and they moved to Mississippi’s only all-black town, Mound Bayou, where he assisted Dr. TRM Howard. lead a boycott. They handed out thousands of fluorescent stickers that read: “Don’t buy gas where you can’t use the toilet.”

In January 1954, the University of Mississippi Law School dismissed Medgar Evers because of the color of his skin. NAACP officials considered taking his case to court, but they were so impressed with him that they hired him as the first field secretary of the Mississippi NAACP.

Myrlie Evers worked as his secretary. She said he insisted they be called “Mr. Evers” and “Mrs. Evers” in the office.

He spent much of his time on the road, putting 40,000 miles a year on his car, recruiting new members, relaunching branches and inspiring young people to participate in the movement, including Joyce Ladner, who invited him to speak before the NAACP Youth Council in Hattiesburg.

“He had a quiet courage,” she remembers. “I was always amazed that he would drive alone at night on the two-lane highways of Mississippi. He was a marked man, but he kept going.

In 1961, Joan Trumpaeur Mulholland was one of more than 400 Freedom Riders, half of whom were white, who challenged segregation laws in the South. She and other riders were arrested and sent to serve their sentences at Parchman State Penitentiary.

When she and other Riders needed a lawyer, Medgar Evers “was the one to do it,” she said.

He became a role model to her and others in terms of character and courage, often speaking to students at Tougaloo College, she recalled. “He wasn’t intimidated.”

In 1962, Evers appointed Leslie McLemore as president of the Rust College chapter of the Mississippi NAACP. “Medgar Evers was truly a brilliant man,” he said. “He had an incisive mind and a personality that drew people to him. In another era, he might have been a U.S. senator from Mississippi or maybe even president.

Evers investigated countless cases of intimidation and violence against black Americans, including the murder of Emmett Till in 1955. Evers often dressed as a sharecropper during these investigations.

No matter where he went, threats of violence followed. He bought an Oldsmobile 88 with a V-8 engine so powerful it would leave most cars behind. On some dark nights across the Mississippi Delta, he put it on the ground to escape those determined to harm him.

His name was on the Ku Klux Klan’s “kill lists” and his home phone rang at all hours with threats against him and his family.

When his daughter, Reena, answered the phone once, she heard a man say he planned to torture and kill her father.

Despite these threats, he stayed. He told Ebony magazine: “The state is beautiful, it’s my home, I love it here. A man’s state is like his house. If it has faults, it tries to remedy them. That’s my job here.

On May 20, 1963, Evers spoke on television about the mistreatment of black people in Mississippi. “If I die, it will be for a good cause,” he told the New York Times. “I fight for America just as much as the soldiers of Vietnam.”

A few weeks later, President Kennedy gave his first and only civil rights speech, telling millions of television viewers: “If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public, please he cannot send his children to the best public school available, if he cannot vote for the officials who will represent him, if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life that we all want, then Who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and he stayed in his place?

Evers smiled. He and other black leaders had urged Kennedy to pressure Congress to pass a civil rights bill, and it now seemed a given.

Hours later, while returning home from a late civil rights meeting, Evers was shot in the back in the driveway of his Jackson home.

Myrlie Evers and their three children rushed outside, saw the blood and screamed. “Dad!” Reena shouted. “Please get up, Dad.”

He never did.

“He had the courage to do an impossible job at a crucial turning point in American history,” said Taylor Branch, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of a trilogy on the civil rights movement.

For the first time, members of the mainstream press did not call such a killing a “lynching,” he said. “They called it an assassination.”

In his book Parting the Waters, he writes: “White people who had never heard of Medgar Evers said his name over and over, as if the words themselves had the tone of legend. It seemed appropriate that the casket be placed on a slow train through the South, bound for Washington, so that the body could lie in state.

After the casket arrived, Medgar Evers was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

“The tragedy of his martyrdom is an eloquent testimony to the courage and dedication of a leader who, during his lifetime, deserved the respect and support of powerful people who later publicly identified with this man and his cause,” he said. said John Dittmer, author of “Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi.” » “Although long overdue, this award is a fitting tribute to Medgar Evers and his family. »

A year after Evers’ assassination, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act on his birthday, and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the bill hours later.

“Medgar Wiley Evers stood boldly against injustice, against oppression, against this country’s determination to keep black people as second-class citizens,” Williams said, “and he was assassinated because of his commitment to truth, justice and the fight for civil and human rights. rights.”

Before leaving office as governor in 1984, William Winter welcomed Myrlie Evers and her family to the mansion, where he remarked that Medgar Evers had done more than just free black Mississippians, he had also freed white Mississippians from the bonds of racial segregation, oppression and hatred. , he said. “We were all prisoners of this system.”

It took three decades before Evers’ killer was finally brought to justice in 1994, and that verdict helped inspire the reopening of other cases. There were 24 convictions in unresolved civil rights cases.

It all started because of Myrlie Evers’ courage to push for justice in her husband’s case, said Leslie McLemore, who helped found the Fannie Lou Hamer National Institute on Citizenship and Democracy. “This wouldn’t have happened without his perseverance.”

When she learned last week about the Presidential Medal of Freedom honoring her late husband, she exclaimed to her daughter, Reena Evers-Everette, “Oh, my God!

Then Myrlie Evers fell silent.

“I am completely speechless,” she said, “and frozen with gratitude.”

Evers-Everette still misses the man she knows how “Dad,” but she perseveres as executive director of the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute because his spirit inspires her.

“I feel it around me all the time,” she said. “I am amazed by his courage, his endurance, his vision and his commitment to equality and justice for his people and for all humanity. I pray for his love and wisdom as I continue this work, because I do not want him to die in vain.

Compete to win the race against time

Enter for a chance to win a signed copy of Jerry Mitchell’s book, Racing Against Time: Journalist Reopens Unsolved Civil Rights Era Murder Cases.

In Race against time, Mitchell takes readers on the winding and frenzied path that led to the reopening of four of the most infamous murders of the civil rights movement era, decades after the fact. His work played a pivotal role in bringing the killers to justice for the assassination of Medgar Evers, the firebombing of Vernon Dahmer, the 16th Street Church bombing in Birmingham and the Mississippi Burning affair.